What Is Really Going On When We Are 'Triggered'?

Sep 14, 2023

What are we really saying when we say ‘I’m triggered’?

Most of us are familiar with the term 'trigger', but it's used in a variety of ways, often without any real clarity about what it actually refers to.

So, in this post we’re going to look at what we mean by the term ‘trigger’ in the context of an understanding of the nervous system.

Being triggered is always a big deal

In terms of the ground we’ve already covered elsewhere in our Core Teachings series, we can describe a trigger as a threat that takes us out of our window of tolerance.

Or put another way, a trigger is something our nervous system responds to by taking us out of somatic safety and into some form of survival response.

Remember that our nervous system developed over millions of years in a world that held the constant potential for dangerous or life-threatening situations.

And our nervous system still interprets threats of all kinds in this high-stakes way.

So, while nowadays a trigger is not necessarily anything actually physically dangerous or life-threatening, the nervous system still perceives or ‘interprets’ all kinds of things as serious threats.

This means that whenever we are triggered, at a neuro-biological level the stakes are always high – being ‘triggered’ is always a really big deal to our animal body, and its responses are matched to that.

With that said, we’d like to introduce the model of the triune brain, to fill out the picture around what happens when we are triggered.

Introducing the triune brain

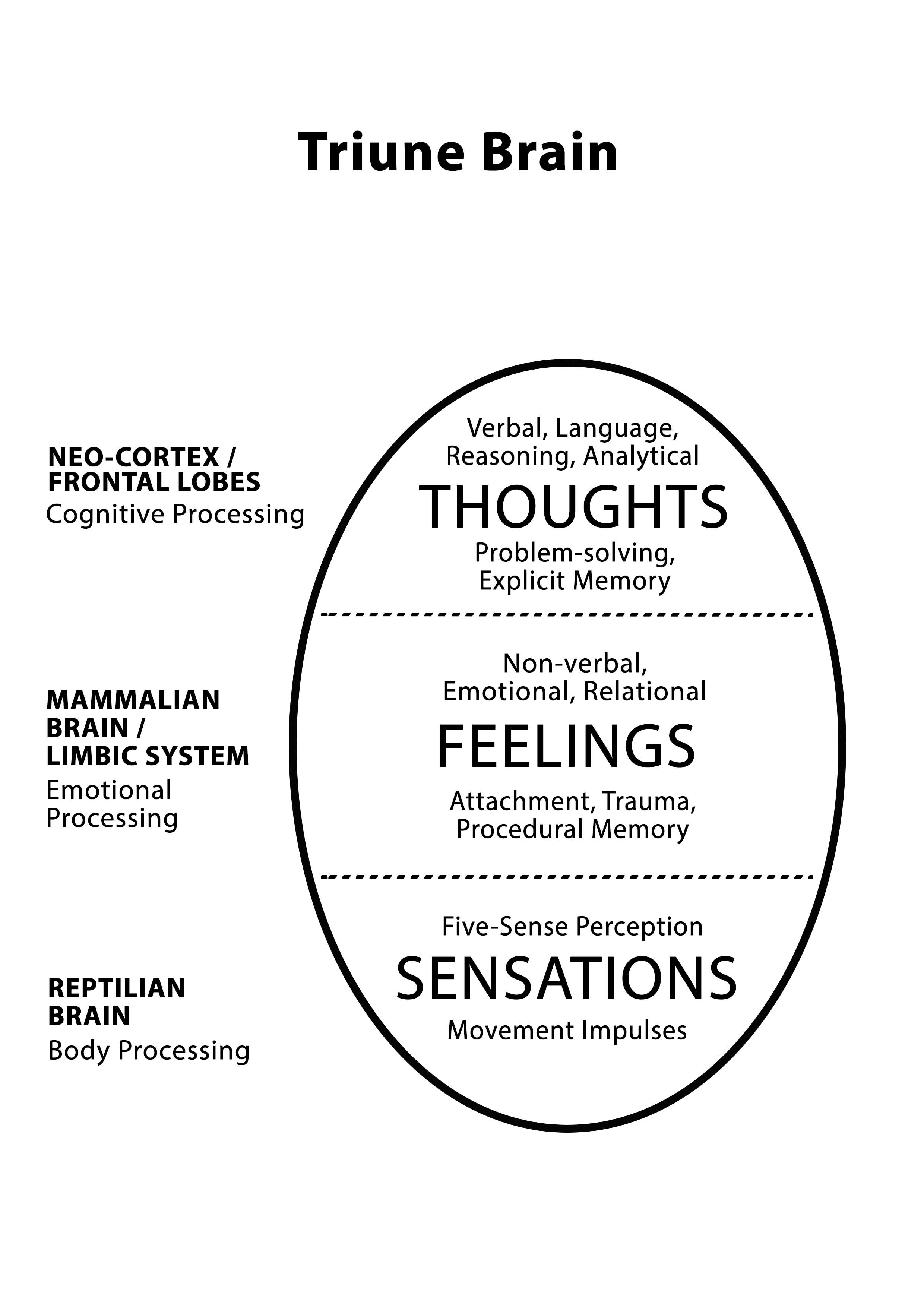

The concept of the triune brain proposes that the human brain is composed of three distinct evolutionary components, each associated with different functions and behaviours.

The model is a simplified representation of the structure of our brain, with the reality being much more complex and interconnected.

But it helps us to understand some basic aspects of brain function and behaviour in an evolutionary context, which can enable us to get more of a feel for what’s going on under the hood of our nervous system, and a better sense of what we experience when we are triggered.

These three components are often referred to as the neocortex, the mammalian/limbic system, and the reptilian brain, and are outlined with their associated functions and behaviours in the diagram below.

Neocortex

The neocortex is the most recently evolved part of the brain and is unique to primates, especially humans. It comprises the outer layer of the brain and is highly developed in terms of structure and complexity. The neocortex is responsible for advanced cognitive functions, including conscious thought, language, problem-solving, reasoning, and decision-making.

Limbic System

The limbic system evolved in mammals and is responsible for emotions, memory formation, and the regulation of basic drives and motivations. The limbic system plays a crucial role in the formation of social bonds, emotional responses, and the processing of rewards and punishments. It influences behaviours related to feeding, reproduction, and nurturing.

Reptilian Brain

This is the oldest and most primitive part of the brain, responsible for instinctual behaviours and survival instincts. The reptilian brain controls vital functions such as breathing, heart rate, and basic bodily functions. It is associated with innate behaviours like aggression, sex drive, territoriality, and the fight-or-flight response.

Hopefully you can see the connection between this model and the map of the window of tolerance.

Broadly speaking, the neo-cortex relates to our experience of somatic safety and being inside the window, while the limbic system and the reptilian brain relate to HYPER and HYPO activation.

Triggers and the triune brain

So now, with all that in mind, let’s take a deeper dive into what it is to be triggered.

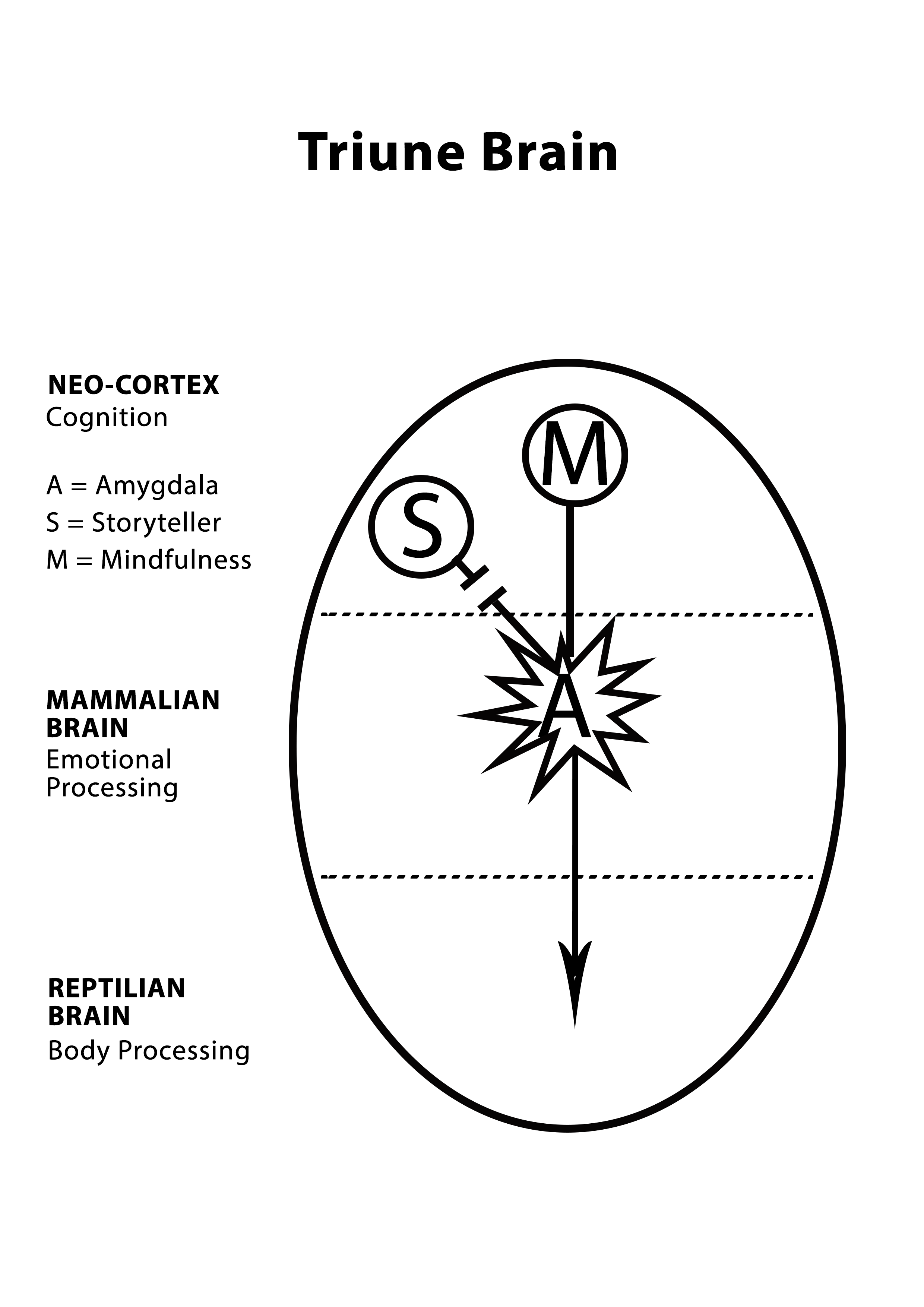

Another diagram will help here.

A key component of the neurobiology of triggers is the amygdala, which lives in the ‘mammalian brain’.

The amygdala is the brain’s ‘smoke-alarm’, a key part of our body’s warning system.

It is constantly on the look-out for signs of danger, and activates whenever it detects potential threats.

Now, what’s super important to understand here is the relationship between this smoke alarm and the other parts of the triune brain.

The amygdala is itself part of the limbic system, but has very strong lines of communication with the reptilian brain.

Whenever it activates, it communicates swiftly and directly with the limbic and reptilian brains, lighting up the instinctual survival responses.

As it does so, the neo-cortex is taken offline.

From an evolutionary perspective this makes sense: in a dangerous situation we want to respond as quickly and instinctively as possible to get us out of danger, not to spend precious time considering what to do.

So when we sense danger, the amygdala switches on our survival responses, bypassing our neo-cortex.

This means that when we are triggered, it’s our limbic and reptilian brains that are driving our behaviour, managing the situation as best they can through instinctive responses and procedural memory.

Our neo-cortex is put very much in the back seat, and its functions – rational thinking, agency, awareness, choice, decision-making, etc – are compromised.

Degrees of activation

It’s probably useful to mention here that there are degrees of activation.

In terms of our instinctual responses, it’s never a simple on/off situation.

Our smoke alarm can send a range of signals from mild threat to red alert, activating our survival responses to different degrees.

All the three brains are always working together to some degree.

But the higher the degree of activation, the higher the degree of auto-pilot, and the less access we have to our higher cognitive functions.

Returning to whole-brain thinking

The model of the triune brain is useful in understanding triggered states, but it’s also valuable in understanding more long-term dissociated states.

As modern humans, we tend to overly rely on our cognitive abilities, particularly on the stories we tell about ourselves and our world.

This is a consequence of a gradual movement away from being fully present in our bodies, in favour of a more mind-based experience of life.

Some suggest that this could be the consequence of cultural trauma accumulated over recent millennia.

But in any case, most of us are now aware that individually we live too much in our heads, and that culturally we are in some important ways disconnected from the body and the earth.

All this is increasingly seen to be having serious consequences for the entire planet.

So in this context, the model of the triune brain shows us that we have overvalued the neo-cortex and its functions, and devalued (and in many instances demonised) the limbic and reptilian brains – the instinctive or animal self.

This split is just as problematic for us as the neo-cortex being taken offline in triggered states.

But the solution to both of these problems is the same: embodiment and the return to whole-brain thinking.

The solution

By consciously understanding and integrating the instinctual self, we can work towards healing the body/mind split and creating more harmony between the various parts of ourselves.

Embodiment practices and somatic resourcing techniques are powerful ways to re-weave our three-part brain back into closer relationship and develop a greater sense of wholeness.

They are also a key part of restoring the sense of safety and bringing our neo-cortex back online after we have been triggered.

In contrast to attempts to deal with activated states through top-down approaches – talk therapies, mental storytelling, many traditional meditation techniques, etc – the somatic approach works directly with our biology and nervous system.

This is important because the neo-cortex doesn’t actually have much influence over the amygdala or the more ancient limbic and reptilian systems, and so is unable to turn off the smoke-alarm once it has been turned on.

But somatic resourcing does have an effective influence over the amygdala.

When we notice we are triggered we can apply our somatic resources of breath, sound, touch and movement to send signals to our nervous system that we are safe, that there is no danger.

In this way we communicate a sense of safety directly to the animal body, which then passes this sense of safety to our limbic brain and on to our whole system – including our conscious experience in the form of emotions and thoughts.

This is the fastest and most effective way to bring the neo-cortex back online, restoring us to our full awareness and cognitive capacity.

It’s this bottom-up approach that is at the core of somatic empowerment.

And it’s not difficult to learn to make this our go-to strategy whenever we become triggered.

Elsewhere in this Core Teachings series we describing how to do so in more detail.